Pilgrims, Mendicants and Beggars

Mendicancy. What exactly is meant by that? Dictionary definitions tend to divide the concept into two broadly different manifestations, being those with an explicit religious purpose which essentially denies a gainful life in the world in favour of a life of renunciation and poverty, and those which are simply related to social conditions of destitution of one form or another wherein life must needs be supported by begging, unrelated to any religious imperative. Mendicancy is really the more apt term for a life of poverty which is, in fact, supported by begging, whilst simply being destitute for any number of reasons, impelling the destitute person into a life of begging is very different, with very many underlying social and psychological dynamics. Life beliefs, life circumstances and presence or absence of ‘choice’ therefore provide strong determinates

The concept of the wandering holyman is certainly not new given the domination of many important religious orders with their related mendicant traditions since the early middle ages in Europe, and Asia more widely, with different Buddhist orders. But religious mendicancy is not peculiar to Christianity, Buddhism, or indeed any religion. In India the sadhu tradition can similarly be traced back into the early medieval period, being one of several theological traditions which are now subsumed within the generic of ‘Hinduism’, although many are Shiva yogis, drawn from an ancient tradition traceable back to Kashmir or Trika/Monist Shivaism, that evolved in the 10th – 11th centuries Common Era [1].

This brief introductory preamble apart, there’s a lot of general information about sadhus and other different orders of religious mendicancy as simply doing a Google search will reveal, so it’s not my intention to make this an academic analysis or repeat general information readily available elsewhere [2]. I have my own personal experiences of sadhus across the principal Pilgrimage years and this is what this post is mainly about.

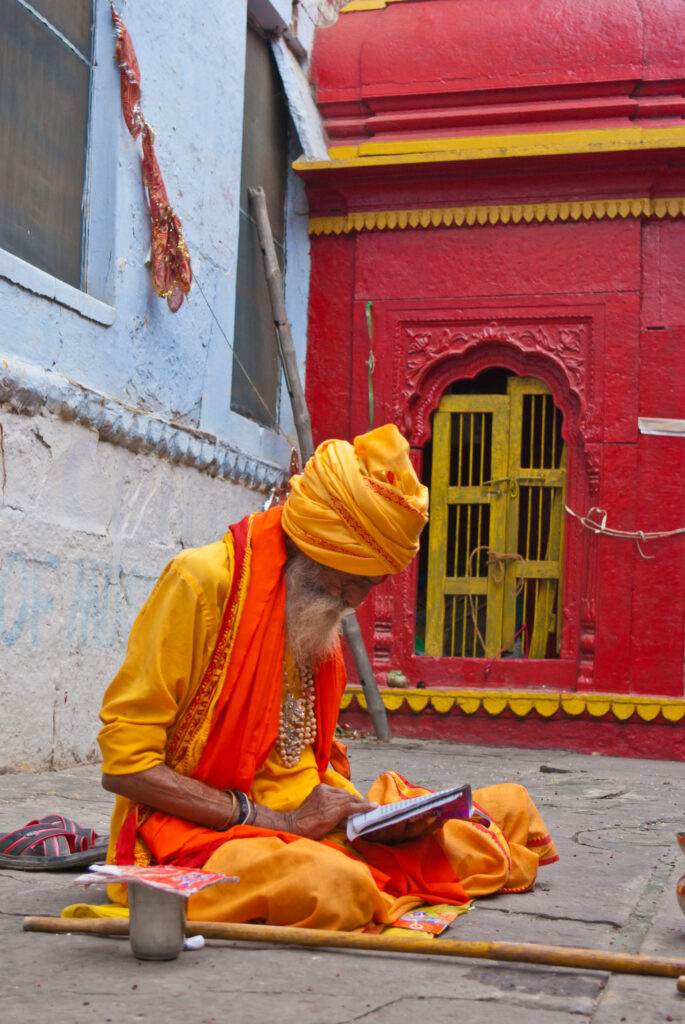

The simple term ‘sadhu’ disguises an enormous variability, both in terms of general appearance, as well as in reasons for becoming a mendicant in the first place. In a land where social welfare provision is largely absent, people who are disabled, or old people without families to care for them may become sadhus by default. Assuming loin cloths, robes and orange turbans, or other distinctive dress, is a way to advertise one’s calling, but I’ve certainly seen many sadhus with crutches, or who are disabled in other ways. At the high temple Muktinath, Nepal during my pilgrimage there in 2021, I saw one man who was missing both his lower forearms, making any normal life of gainful employment impossible, leaving a life of mendicancy his only option to live with some degree of dignity.

Back in the pandemic year of 2020, during the summer long Indian lockdown I was caught up in, I mistook one old man who wandered the streets dressed in dark maroon coloured robes as a sadhu and later learned he was a homeless alcoholic whose family had thrown him out because of his drinking. He was always begging for ‘alms’, though I understood later to support his drinking habit. I had actually spoken to him at length on one occasion and he seemed a well educated man, but sadhu he most certainly wasn’t. But I knew little enough about sadhus then, they were a distant sort of concept and I hadn’t really been in India long enough to have had much of an exposure to them, excepting perhaps during my visit to Varanasi in mid March of that year, just before the pandemic struck seriously, where there were many older ones who had ceased their wandering and had become sedentary on the ghats, waiting for death to come to them perhaps.

For me the dark side of mendicancy of this nature lies just exactly in the word, denoting need to beg for alms. This fairly guarantees that a sadhu will be constantly having to find food, and therefore any route (such as here on the road to Gangotri) or pilgrimage destinations such as Rishikesh with significant numbers of sadhus will have a big impact on the people living there. Foreign visitors attract particular attention and walking through the streets of towns like Rishikesh is to run the gauntlet of being accosted many times with the demand for alms. Refusal can attract abuse. Local merchants, particularly vendors of street food, must suffer significantly from being regularly importuned by the street sadhus for “one chapati” or “one chai”, representing a significant drain on what must of necessity be very narrow profit margins and the need to support families at home. But increasingly modern mendicants expect alms to be given in the form of cash, not food. On one occasion I was able to save some of my breakfast in a hotel restaurant to take out to give to an elderly man whom I had seen outside, who clearly looked in need of a meal. By the time I emerged he had been replaced by a sadhu, who looked contemptuously at the proffered food and demanded I give him money instead. Many people are actually afraid to refuse them, given that sadhus, especially the Shivas, have attracted a reputation associated with the dark arts and sorcery, something coming from their earliest origins. I have spoken with people apparently terrified of them, incase they used their dark powers against them or their family.

So what of pilgrims then, and how are they different from sadhus? Living here on a key Chota Chardham pilgrimage route, you see a mixture of both regular sadhus, whom one might see as lifelong pilgrims, and regular pilgrims, who are people taking time out to conduct a spiritual journey to some key destination of particular significance, such as Gangotri here. Sometimes they may be difficult to distinguish given people undertaking pilgrimage frequently wear distinctive dress for the period. But there are many folk who simply wear standard ordinary clothing and are therefore indistinguishable from a regular tourist.

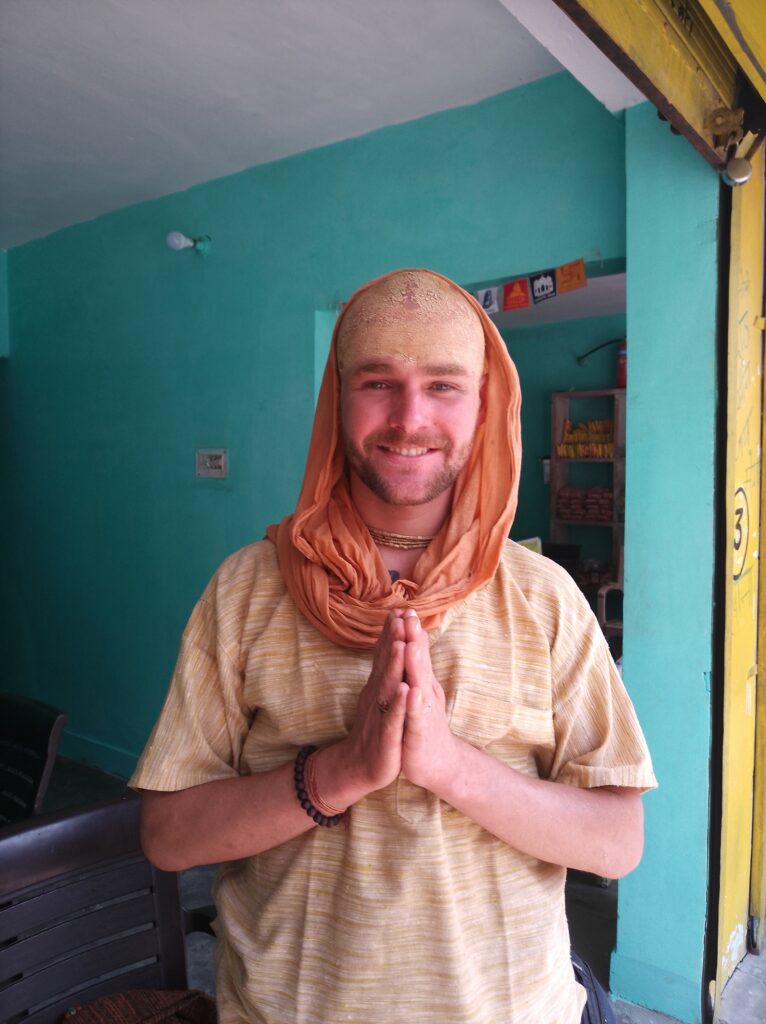

I met one young man recently who was on his way up to Gangotri, clearly a westerner but wearing a lungi and with the distinctive white ochre plastered on his forehead. He had been raised in a contemporary Indian spiritual tradition by his mother and was even then atached to a guru, who presumably guided his life pathway and spiritual studies. Although not resident in India, he travelled to the country many times. He clearly was a pilgrim, as indeed I have also been a pilgrim throughout these last four years, travelling to different temples and sacred sites as part of my Pilgrimage journey [4].

[1] See Christopher Wallis, 2013. Tantra Illuminated. The Philosophy, History, and Practice of a Timeless Tradition.. Mattamayūra Press

[2] See for example: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sadhu and the many related links.

[3] By Antoine Taveneaux – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24482280

[4] See In the Spirit. A Journey to Self.

For further information on the sadhus of Rishikesh see: https://www.farfeatures.com/features/2017/11/16/sadhus-of-rishikesh

Off Grid Living

The Song is Over

You May Also Like

A Work in Progress

August 7, 2024Off Grid Living

May 6, 2024